Strategies

of Enfreakment:

Representations of Contemporary Bodybuilding -

Niall Richardson

In

an article in Flex magazine, published in 1992 [August], IFBB professional

bodybuilder Mike Matarazzo wrote that, 'Consensus has it that I'm a freak. To

the general public, I'm an object of ridicule . . .' but 'I love being a

grotesque horrifying freak. I just love it! To me, this is bodybuilding.'

Describing himself in terms such as 'gross' and 'nauseating', Matarazzo

explained how bodybuilding fans delighted in his "freaky" dimensions

which he described as 'huge gobs of twisted, sickening muscle hanging off my

body'. Matarazzo detailed how his unclassical grotesque body was a source of

great pride rather than shame as 'what's especially great is having freaky

bodyparts. It makes me feel unique, as though out of the entire world, I have

something very special to offer, even if it is a quality as weird as mutant

muscularity.'

Another

example from around the same time was the lesser-known professional bodybuilder

Troy Zuccolotto who, writing in 1988, expressed his lifelong ambition as being,

'I want to be big. I mean, so huge it'll make you puke! I want to be gross!'

(Sport and Fitness: Incorporating Health and Strength, December 1988).

Similarly,

in a 1989 edition of Flex, Franco Santoriello, another young professional

bodybuilder, is described as 'a fissiparous freak of frightening size, a

perpetual shock wave of emotional tumescence that threatens to annihilate all

life forms that wander within the range of his fallout.' Adam Locks lists the

type of descriptions which bodybuilding publicity material would employ in

representing its stars: 'Freak-enstein, Meat Monster, White Buffalo, Freaky

Guns, Monster Mass, Jurassic Thighs, Thunder Thighs, Humungous Hams,

Cantaloupe-Size Delts, Titanic Thighs, Monstrous Delts, Bulldozer Quads, Canons

(for biceps), and Barn Door Shoulders (Locks, Adam [2003], Bodybuilding and the

Emergence of a Post Classicism).

What

we find expressed here is the celebration of abject freakishness: a

representational tactic which would become the norm for the world of

contemporary competitive bodybuilding.

Welcome

to the strategies of enfreakment used to market contemporary bodybuilding.

As

this book's introduction has detailed, there was a move in professional level

competitive bodybuilding from the ideal of the classical physique to the

disproportionate or "grotesque" physique. While the classical ideal

celebrated symmetry, proportions, and overall aesthetic harmony of the body,

the "post-classical body" is an inharmonious shape in which certain

parts have been distended so that they are too large and therefore overpower

the rest of the physique. Arguably, the first example of bodybuilding's

celebration of this body type was Tom Platz, whose extreme quadriceps

development overshadowed the rest of his body and managed to make even his hugely

muscled torso appear small. Possibly, Larry Scott was the first to anticipate

this move given the size of his arms, but it was Platz who became the first

main example of the post-classical physique. After Platz, bodybuilding

publications would marketing other bodybuilders having "freaky" and

grotesque muscle groups, including Eddie Robinson (famous for his arms), Dorian

Yates (famous for his enormous lats - back), and Platz's successor Paul

"Quadzilla" DeMayo. In other words, what was being sold to the

"fan" or "consumer" of bodybuilding representations was no

longer the pleasure of gazing upon a 'perfectible body' (Dutton, Kenneth [1995]

The Perfectible Body: The Western Ideal of Physical Development), but the

thrill of staring at a grotesque body. Indeed, terms which would enter into

bodybuilding currency would include 'monster,' 'grotesque,' 'gross,' and, most

importantly, 'freak.' From the late 1980s onwards, professional bodybuilding

was "sold" to the consumer through the representational strategy of

enfreakment.

What

is a "Freak"?

In

my last monograph, Transgressive Bodies: Representations in Film and Popular

Culture (2010), I suggested that the archaic entertainment spectacle of the

freak show has been creeping back into contemporary popular culture - if,

indeed, it ever left. The most influential writers on freakshows have been

Leslie Fiedler (1978), Robert Bogdan (1998), Rosemarie Garland Thomson (1996),

Rachel Adams (2001) and, most recently, Nadja Durbach (2009). One of the main

critical points to remember when considering freak shows is that the

"freak" is always a construct. The body may be different - for

example, it might be extremely tall - but it is the mechanism of the freak show

- the strategy of representation - which renders this body a "giant."

As Bogdan explains, '"freak" is a way of thinking, of presenting, a

set of practices, an institution - not a characteristic of an individual.' For

example, in most freak shows there was usually an exhibit entitled "the

giant." This was a man who was undoubtedly very tall, yet his tallness was

re-presented to the public as "giantism" and so the presenters would

usually have the "giant" wearing shoe lifts to give him another few

inches and a hat to add to the impression of extreme height, while the mise en

scene of the stage would also conspire to increase the illusion of even greater

height through the use of under-sized furniture. Likewise the "world's

fattest lady" always gained quite a few pounds in the program blurb and

through padding under the clothes. As Bogdan explains, in the freak show,

'every person exhibited was misrepresented to the public. The critic David

Hervey aptly describes this process of stylizing and, most importantly,

marketing the non-normative body as 'enfreakment.' (Hervey, David, [1992], The

Creatures That Time Forgot: Photography and Disability Imagery).

Of

course, the above debates raise the question of why spectators are still

interested (perhaps even more than they ever have been) in staring at

"freaks." Leslie Fiedler adopts a totalizing psychoanalytical

approach and makes the valid argument that freak shows bring to life our

darkest, most secret fears. For example, we stare (not look or gaze) at the

dwarf because this body touches our darkest fears about never growing up and

remaining a child forever. Yet this nightmare is made safe as it is removed

from us, contained within the representation (the freak show stage - or the

contemporary film/media text) and establishes a "them and us"

boundary. Nevertheless, as we stare at the 'freak" we shiver with anxiety

as we are reminded that this "difference" may not be as firm or

clear-cut as we like to imagine it is. (Fiedler, Leslie [1978] Freaks: Myths

and Images of the Secret Self).

Although

Fiedler makes a valid argument, psychoanalysis makes little allowance for

cultural variation (some cultures, given the specifics of its cultural history

may have a greater fear of the image of, say, "the fat lady" than

others) and also this does not suggest why "freaks" seem more popular

now than they ever have been. More recently, critics such as Margrit Shildrick,

Rosemarie Garland Thomson, and Rachel Adams have developed Fiedler's argument

by pointing out that the concept of the freak is a fluid one which continually

evolves in relation to cultural norms. In other words, the "freak" of

the dwarf may signify differently in relation to contemporary spectators than

the way it did for spectators of the Victorian freak show. As Adams points out

'the meaning of freaks is always in excess of the body itself' (Adams, Rachel

[2001] Sideshow USA: Freaks and the American Cultural Imagination). There is no

fixed meaning to the body of the freak because there actually is no essential

body which exists prior to the discourse which "creates" it. The freak's

body is the product of the institution or discourse known as the freak show. As

Thomson explains (Thomson, Rosemarie Garland - Cultural Spectacles of the

Extraordinary Body; Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in

American Culture and Literature; Staring: How We Look), the freak show exhibits

become 'magnets for the anxieties and ambitions of their times'. These

'magnets' can function as abject sponges, absorbing all the fears and worries

of the particular period. As such, the signification of the "freaks"

and ways in which they have been exhibited have evolved over the years.

However,

why "freaks" may have returned in popularity in recent years may be

due to a growing realization on the part of the general public of the key

theory in body studies: that there is no fixed, inherent or essential body.

Arguably, the media's fascination with the "freak" body - the 500 lb

teenager; the woman with the most augmented breasts in the world; the

self-elective eunuch; the most beautiful transsexual in the world - is that

these images remind us (perhaps subliminally rather than explicitly) that the

body is not an essential attribute but instead is shaped by culture. A key

difference, of course, is that in recent years we have seen a growth in the minor

category of "freaks" which Bogdan (Freak Show: Presenting Human

Oddities for Amusement and Profit) identified as the 'self-made freak'. At the

heyday of the freak show, these were "freaks" such as the excessively

tattooed person, the person with innumerable piercings or the sword swallower

or the fire eater; in other words, bodies which had no physiological difference

but who enhanced/modified their bodies or forced their bodies to perform

extreme actions. Given advances in science, surgery, medicine, technology and -

most importantly for this chapter - exercise and nutrition, one of the things

we are witnessing is a growth in the category of the self-made freak. (Examples

of two famous self-made freaks have been the late Lolo Ferrari and the late

Michael Jackson). Therefore, what a documentary focusing on a woman with the

most surgically enhanced breasts in the world is not the terror of a freak of

nature but the horror of the overwhelming power of contemporary regimes of

culture in shaping the body. This documentary reminds us that the body is

formed through specific discourses and, in the case of a woman such as Lolo

Ferrari, shows us how frighteningly powerful these discourses can be. If these

discourses are the way the woman identifies - Lolo Ferrari, for example,

identified only in terms of her augmented mammary glands and was 'the woman

with the world's largest breasts' - then the body will be formed in accordance

with the cultural demands. Ferrari had to have more surgery to accede to the

ranks of having the most augmented breasts in the world. What Ferrari

demonstrated, in a nightmarish fashion, was how the human body was shaped

specific cultural discourses; performatively constituted by the discourse of

surgically enhanced breasts.

Arguably,

the same thrill is the case when we stare at the bodybuilding

"freaks" in the Mr. Olympia line-up. We marvel at the demands of

contemporary bodybuilding culture which has forced these bodies to develop to

such extreme proportions. While Schwarzenegger had competed in the Mr. Olympia

at about 230 lbs and at a height of 6'3", the 2010 Mr. Olympia - Jay

Cutler - weighs in at about 270 lbs at a height of 5'9". More than any

other contemporary activity, professional level bodybuilding testifies to the

overwhelming power of culture in shaping and coercing the human body to the

dictates of specific regimes.

However,

given that bodybuilding representations are hardly mainstream (a bodybuilding

training DVD will never make Amazon's top seller list), it is fair to say the fans

of these representations have considerably more investment and, in most cases,

identification in these "freak" bodies than a spectator who, surfing

through the television channels, stumbles across a documentary about a woman

with the most surgically enhanced breasts in the world. It is this

investment/identification which makes this particular strategy of enfreakment

markedly different from other contemporary representations.

Enfreakment:

Markus Ruhl

As

I have emphasized already, "freak" is a re-presentation (a

misrepresentation) of an unusual or non-normative body in which this body's

difference is coded as "freakish." Undeniably, the professional

bodybuilder quoted at the start - Mike Matarazzo - is an exceptionally

(unusually) muscled man who has body parts which are disproportionately bigger

than the rest of his physique. However, it is only the representational

discourse which renders this unusual body a "freak." In other words,

"freaks" only "exist" as re-presentations.

This

has particular relevance for bodybuilding given that (as outlined already in

the introduction to this part) the world of extreme, competitive bodybuilding

only exists for the majority of people as representations. These competition-ready

bodies, so stripped of fat and dehydrated that their veins look like snakes

slithering underneath paper-thin skin, only look this way for a short period of

time and so the majority of people only "know" this body because of

representations. Most competitive-level bodybuilders do not walk around in

public, flaunting their extreme muscularity in tank-tops and training vests but

tend to cover their vast bulk with loose clothes, known in bodybuilding circles

as "baggies." As Adam Locks points out, the bodybuilder, dressed in

baggies, looks to the general public as someone who is merely bulky or fat and,

as we all know, in our contemporary culture of fast-food plenty, bodies which

are bulky or "overweight" are hardly unusual, let alone warranting

the status of "freak."

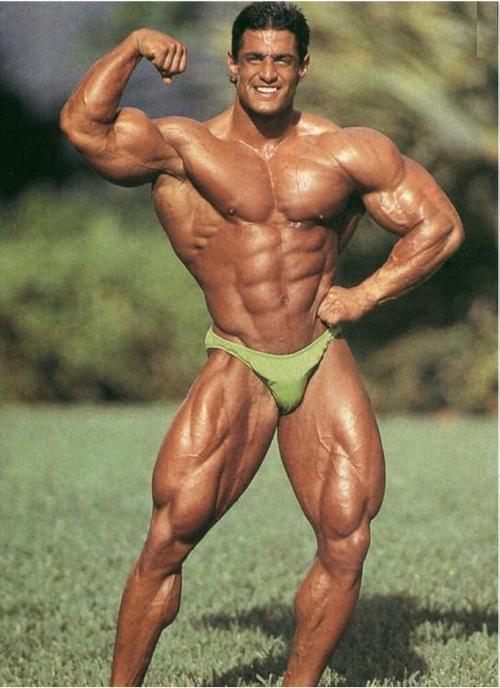

Bodybuilding

representations, however, have strained to represent the extremely muscular

body as a "freak." One contemporary star of the professional

bodybuilding circuit, who has been subject to bodybuilding culture's strategies

of enfreakment, has been the German bodybuilder Markus Ruhl, an athlete

(in)famous for the sheer enormity of his physique. Although never having been

crowned Mr. Olympia, Ruhl continues to attract a legion of fans enthralled by

the huge dimensions of his body. Jon Hotten (Muscle: A Writer's Trip Through a

Sport With No Boundaries, 2004) employs enfreakment discourse to describe Ruhl

as having 'no real neck to speak of, although there must have been one

somewhere. His lats were so big his arms had nowhere to go but outwards. His

thighs moved past one another like two men in a narrow corridor.' Indeed, it is

hardly surprising that Ruhl's nickname is 'Das Freak.' In a description of the

free-posing round of the Mr. Olympia, one journalist describes Ruhl as 'Das Freak!

One of the more popular bodybuilders to grace the posing dais in recent years.

Ruhl was his usual beastly self. Freakish, hard and separated, Markus is

finally getting his props and deserved his placing.' This element of Ruhl's

freakishness is the way bodybuilding publicity material always

"markets" his body, especially in his lifestyle DVD.

Lifestyle

DVDs are publicity material for professional bodybuilders. These documentaries

are, unsurprisingly, composed of sequences of the bodybuilder training in the

gym, and talking about his exercise regime and diet, but will also feature

sections which represent the athlete in his recreational leisure time. In

Ruhl's first publicity DVD, Markus Ruhl: Made in Germany, the documentary

features all the usual sections of gym training, nutrition, and competition

preparation but also includes a rather entertaining segment entitled 'Ruhl Goes

Shopping,' which represents Ruhl and his wife, Simone, out shopping for their

groceries in the local supermarket. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mAOuIqXJwb0

The

humor of this sequence is observing the stares which Ruhl receives from all the

other shoppers. As the sequence begins, Ruhl, dressed in training tank-top and

workout pants, lumbers along the aisle pushing his shopping trolley.

Diegetic

"musak" plays, suggesting the everyday banality of the situation. It

is also intended to suggest the "virtual-realism" of the sequence and

to downplay that this is an "enfreakment" marketing scenario, used to

sell the image of Ruhl to bodybuilding consumers. As Ruhl swaggers around the

supermarket, filling the trolley with huge quantities of groceries, he manages

to turn every head in the place as people stare in astonishment, unable to

fathom what this body actually is. Some people giggle, some simply stare and a

few more arrogant individuals feel it is their right to make jokes about the

man's extreme proportions. The sequence culminates in Ruhl queuing at the

check-out while a woman standing at the next queue is visibly nauseated by the

sight of Ruhl's body. The woman makes the classic "stifling vomit"

face and clasps her hand to her mouth as if to stop herself from puking. It is

interesting that this particular moment was deemed so important to the whole

documentary that it was used in the trailer and, should the spectator fail to

notice that a woman was nauseated at the sight of Ruhl's "monstrous"

body, this was even highlighted on the screen by an arrow superimposed onto the

image.

Of

course, one way of interpreting the shopper's stares is to rad their

astonishment due to a masculine invasion of a gendered space. Some could argue

that Ruhl's shopping is a hyper-masculine invasion of a feminine space and

therefore this produces horror, if not even nausea, by the female occupants.

Since the iconic ending of The Stepford Wives, in which a troupe of gorgeous,

pre-feminist women (or are they androids? - we never really know) navigate

their way around Stepford supermarket in a sequence of such beauty that it

almost looks like a finely choreographed ballet, the supermarket may be read as

an exclusively feminine space. In this respect, the 'shopping sequence' is

almost akin to a masculine invasion of the feminine. This (arguably)

hyper-masculine body invades a space which is normally a safely feminine haven

and intimidates, if not even terrorizes, female shoppers.

However,

reducing the supermarket to an exclusively feminine space is, in contemporary

culture, not accurate. It hardly requires a quantitative investigation to

discern that supermarkets are now frequented by men as well as women although,

certainly in some areas, the majority of shoppers will undoubtedly be female.

Instead of viewing the supermarket as indicative of femininity, it is probably

more appropriate to consider it in terms of the banal, the everyday or, more

importantly for these debates, the normative.

Therefore,

I read the 'Ruhl Goes Shopping' sequence in the DVD as a celebration of how

this body no longer 'fits' (quite literally in his case) into the regimes of

the normative. Through his intense program and training and supplementation

Ruhl is represented as having built a body which has transcended the everyday

and therefore upsets the normative bodies of the supermarket who find his body

impossible to read. In this respect, extreme bodybuilding is represented as

attempting a form of deconstruction, offering a challenge to accepted ideas of

beauty.

Arguably,

extreme bodybuilding could be related to other body modification practices such

as tattooing and body piercing. Like bodybuilding, tattooing and body piercing

can be interpreted as a form of resistance, critiquing (often through

caricature) culture's notion of normative beauty. In one respect, what the

extreme body-piercing practitioner does is to take something which is deemed

attractive or ornamental by contemporary culture (pierced ears are usually

regarded as attractive ornamentation) and then caricature this through

excessive piercing. Pierced ears are deemed "sexy" by normative

Western culture but what if nose, lips, cheeks, and eyebrows have piercings in

them as well? Similarly, tattooing can have a comparable trajectory. If

contemporary Western society deems one subtle tattoo to be a risqué, quirky

ornamentation, what about when the body becomes covered with these "ornaments"?

Arguably,

a comparison could be drawn between the politics represented by the hyperbolic

body of the extreme bodybuilder and another embodiment of cartoonish

dimensions: the late Lolo Ferrari. Ferrari was a Belgium porn star who attained

a relative degree of notoriety for having (while she was alive - I believe she

has been succeeded now) the most surgically enhanced breasts in the world. She

sprang to media recognition largely because of her regular appearances on the

British television show Eurotrash where she did very little else other than

flaunt her enormous breasts for the spectator's attention. Ferrari's slot on

Eurotrash was entitled "Look at Lolo" and every week spectators would

marvel at hos such an extreme body could manage to do a basic chore such as

polish the silver or wash a car. Ferrari's breasts were indeed

"freakish." After a huge number of operations (18-25 - reports vary),

Ferrari had indeed attained the dimensions of a living Barbie doll. Reports

(but, again these may simply be 'enfreakment' marketing ploys) suggest that she

suffered intense back pain, from supporting the weight of the breasts, and had

trouble sleeping at night. Ferrari died of a drug overdose - or so the reports

suggests, but this is open to debate and many believe that her husband was

implicated in her untimely suicide. While most critics would simply dismiss

Ferrari as a woman suffering from serious mental health issues, most obviously

body dysmorphia, Meredith Jones (in Body and Society) makes some very interesting

points about the politics of Ferrari's cartoon dimension breasts by suggesting

that Ferrari's surgically enhanced body can be read as transgressive. By having

attained the dimensions normally associated with a Barbie doll, or a masculine

fantasy cartoon, Ferrari is actually making an ironic comment on the

"perfect" woman's body. If society deems the extreme dimensions of

tiny waists and enormous breasts as the feminine ideal, the representations of

Ferrari ask how attractive it is when when these dimensions are exaggerated to

cartoon proportions. As Jones points out, 'Ferrari was quite aware of the

borders she was transgressing' as something deemed ideal in feminine beauty can

become very unattractive, if not even ugly, when it reaches excessive dimensions.

In this respect, Ferrari was enacting a form of femininity that was 'overly

subversive'. Like the extreme bodybuilder, Ferrari can be read as a 'freak of

conformity' in that she takes something which is deemed ideal in contemporary

culture but twists or even carnivalizes it.

Arguably,

the extreme bodybuilder can be read in a similar fashion. This celebration of

the 'freakish' body, a body which has pushed idealized proportions to a

ridiculous extreme, can be read as making a subversive comment on idealized

masculinity. Most importantly, as the 'Ruhl Goes Shopping' sequence

demonstrates, male bodybuilding is represented as celebrating a rejection of

traditional ideas of attractiveness.

Of

course, a comparison with Lolo Ferrari obviously ignores the issue of gender.

When a man challenges regimes of masculine attractiveness/beauty it is not the

same cultural taboo as when a woman does it. While women have always been

considered simply as their bodies, and their appearances have always been

policed by patriarchal culture, men by contrast have had the liberty (until

recently) of not having to be overly concerned about their appearance. The male

body is a tool for getting the job done but never something that should be the

cause for concern about whether or not it is beautiful (Bordo, Susan [1999] The

Male Body). Yet this links to one of the tensions within bodybuilding in that

the appearance of the body is the ultimate goal of the bodybuilder. Unlike

powerlifting or weightlifting, which are concerned with the ultimate heavy

lift, irrespective of how this alters body's appearance, bodybuilding is not

concerned with the amount of weight lifted as long as it effects changes in the

physique. Therefore extreme bodybuilding stands as a curious activity given

that its concern is purely appearance - the bodybuilder works out to create a

specific body shape and not to achieve maximum strength - but that this

"appearance" is excessive and unattractive by contemporary culture.

It

is important to remember that the sight of Ruhl's body is represented as

managing to evoke nausea in a woman queuing at the checkout but yet this abject

spectacle is represented to the bodybuilding fan (who, arguably, wants to copy

Ruhl's training and nutrition so that he too can look like that) as something

desirable. Therefore, it is not rather odd that this sequence proclaims to the

bodybuilding fan that looking like Ruhl will only lead to public shame and

ridicule? If you look like this, everyone will stare rather than gaze. To

reference Matarazzo once again, you will be an 'object of ridicule' and a

'grotesque, horrifying freak.' It is here that I wish to consider how these

enfreakment representation strategies fuel fantasies of bigorexia in the

bodybuilding fan.

Bigorexia

The

term 'bigorexia' is derived from the established medical term known as anorexia

nervosa. While the anorexic believes that the body is too fat, the bigorexic

believes that the body is too skinny and seeks to increase overall (muscle)

bulk. Obviously, there are very different political and psychological agendas

between anorexia and bigorexia which I consider in more detail later.

However,

there is still some debate about the term bigorexia itself given that some

critics use it as a synonym for "The Adonis Complex" while others,

myself included, draw a distinction here. The Adonis Complex was a term made

famous by the trans-academic text of the same name which argued that more and

more men are now feeling victim of the beauty myth of contemporary culture. Besieged

by images of perfected bodies and six-pack abs in every advertising image, men

are starting to feel the tyranny of impossible standards of beauty in a way

previously experienced only by women. One of the most interesting examples

cited in the Adonis Complex has been the recent transformation in the physiques

of boys' toy dolls - especially action figures. The original GI Joe, Luke

Skywalker, and Hans Solo had body types which could be deemed

"average." By contrast, contemporary models of these toys now display

pumped biceps and washboard stomachs. This fetishization of chiseled

muscularity in popular culture has, arguably, exerted an influence on male body

image and induced an obsession with the appearance of the body in a fashion

similar to those which women have labored under for years.

Yet

I should draw a distinction between the Adonis Complex and bigorexia. While the

Adonis Complex aspires to a body type which is deemed beautiful by the

standards of contemporary culture, bigorexia fetishes "extreme"

muscle mass, often to the point of excess, which moves the body beyond the

spectrum of traditional attractiveness. The bigorexic reveres Markus Ruhl or

the other "mass-monsters" of the professional bodybuilding circuit

while someone consumed by the Adonis Complex aspires to the

"beautiful" dimensions of a Calvin Klein model. In this way bigorexia

can be read as relating, in some respects, to anorexia although there are

definite political differences.

On

an obvious level both bigorexia and anorexia are about the subject gaining

control of the unruly, wayward body. Many people who suffer from anorexia often

feel that their lives are out of control and the only thing that they actually

can control and discipline is the living tissue of their bodies. Bodybuilding

obviously holds a similar trajectory which explains its popularity in prisons,

and other establishments where civil liberties are denied, and also areas of

socioeconomic deprivation. As Susan Bordo explains, like anorexics,

'bodybuilders put the same emphasis on control: on feeling their life to be3

fundamentally out of control, and on the feeling of accomplishment derived from

total mastery of the body' (Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and

the Body [1993]). Yet there is another area deserving attention in the

similarity between the two - the correspondence these activities have to sexual

attractiveness and the awareness the subject has of this. Although, on the one

level, anorexia can be read as women simply trying to adhere to the standards

of beauty found on the contemporary catwalks (where womanly curves have been

replaced by reed-thin, if not skeletal-thin, models), it is also possible to

see anorexia as a form of resistance. Many anorexic women talk about hating the

sexual characteristics of their body. Bordo quotes an interview with one

anorexic woman who describes how, at puberty, she hated the development of her

womanly curves and other sexual attributes such as full breasts. Indeed, many

anorexics express a desire to be removed from the constrictions of sexuality

altogether and of remaining in a time (childhood) where sexuality was not an

issue.

Arguably,

this idea of being removed from the dictates of sexuality is also at work in

the agenda of the extreme bodybuilder or bigorexic. While the anorexic wishes

to subdue her womanly curves so that she is not recognized as a sexual subject,

and not driven uncontrolled sexuality herself, the bigorexic wishes to step

outside the regimes of sexual attractiveness too but obviously in a much more

confrontational, aggressive fashion. The anorexic wants to become small and

unnoticed; the bigorexic wants to become so "gross" that he is

unfathomable within the dictates of sexuality. This is why bodybuilders such as

Troy Zuccolotto (quoted at the start) express a desire to disgust people, to

the point of puking, by his enormous, grotesquely muscled physique. Certainly a

distinctly different agenda from that expressed by someone held in the thrall

of the Adonis Complex, idolizing the beautifully sculpted musculature of an

Abercrombie and Fitch model.

One

of the most outspoken ambassadors of bigorexia is bodybuilder Greg Valentino.

Known for having the biggest arms in the world, Valentino is famous for a very

disproportionate physique (the arms are far too big to be in any way

proportionate to the rest of the physique), and, more recently, for the trauma

his arms suffered as documented in The Man Whose Arms Exploded. In the film,

Valentino explained that he wanted to have the biggest arms in the world so

much that he not only performed site injections of steroids (injecting steroids

directly into the biceps muscle) but also pumped huge amounts of an oil known

as synthol into the muscles in order to inflate them to enormous proportions.

Unable to cope with the sheer volume of synthol, Valentino's arms, quite

literally exploded when his immune system decided it could no longer tolerate

this foreign oil being pumped into the body. His biceps developed internal

abscesses which eventually burst and oozed out. This rather disgusting image -

indeed it would not be out of place in a gross-out horror movie - has delighted

and intrigued many fans, most notably teenage boys. Valentino has appeared

regularly in teenage, gross-out lad magazines such as Nuts and Zoo which often

delight in the horror of exploding bodies, pus and gore, and also the

scatological delights of piss and shit. These abject substances are, of course,

notoriously the fascination of prepubescent boys who often delight in all

things disgusting and gross, especially when they are the cause of the disgust

themselves. In the documentary about steroid use in American sports, Bigger,

Stronger, Faster, Valentino explains that he was not interested in bodybuilding

to make himself more attractive to women. Indeed, with a grin of satisfaction,

Valentino proclaimed that his arms are disgusting and put women off. His face

breaks into a beaming smirk when he describes how women look at his arms and

think 'Gross.'

This

rejection of sexual attractiveness, of building a body which is outside the

regime of sexual allure, obviously accords with the anorexic's trajectory of

preventing the body from being sexual. Of course, the anorexic tries to prevent

the development of sexual features while the bigorexic seeks to exaggerate

features which are deemed sexy, such as gym-sculpted biceps, and caricature

them to an unattractive extreme. It could be suggested (although without

ethnographic research this is speculative) that bodybuilding representations

therefore support homosocial fantasies in which men create their bodies to

impress other men and disgust women. In this respect, it is hardly surprising

that the most avid fans of bodybuilding are pubescent boys, being at extremely

difficult points in their lives - the onset of hormones, lust and the

"threat" of girls - may find some solace in the fantasy

representations of bodybuilding as "removed" from the dictates of

conventional sexual attractiveness. Arguably what can be interpreted from the

representations - or rather enfreakment fantasies - of bodybuilding imagery is

the dream of a petulant rebellion against societal norms. The bigorexic is

saying he will not conform to this tyranny of making his body conform to

dictates of masculine attractiveness - will actively reject the tyranny of the

Adonis Complex - but will make his stand of resistance through the very

mechanisms which the Adonis Complex says men should do; namely, gym training

and bodybuilding.

Why

the Move to Bigorexic "Freak" in Contemporary Bodybuilding?

The

question this "look" raises is why the change in iconography of

bodybuilding representations? From representations which had revered the

proportions of classical beauty they have become images which glorify the

"grotesque" and the "freaky." The reason for the change

might be attributed to various developments in the sport and fitness industry

and cultural politics.

First,

a factor which has undoubtedly influenced the extreme hypertrophy of

contemporary male bodybuilding physiques is the development outlined in this

book's introduction: the growth in popularity of women's bodybuilding and, most

importantly, the change in female bodybuilding physiques. Indeed, while the

developments in nutrition, pharmaceutical enhancements, and training techniques

promoted changes in the physiques of male bodybuilders, it also permitted

extreme advancements in female physiques. As female bodybuilding started to

change, with female bodybuilders attaining a degree of muscularity which

previously was considered only possible for a male body, male bodybuilding had

to progress alongside it.

Second,

the late 1980s saw the growth of a new strand of male body type springing into

public view. This was a more lithely muscled, toned and, most importantly,

eroticised body which came to grace the cover of other alternative health and

fitness magazines and started the cultural trend already described in 'The

Adonis Complex.' As Susan Bordo summarizes, by the late 1980s, 'beauty

(re)discovers the male body.' Eventually this type of body would be canonized

as the Men's Health magazine physique - a body which is distinguished by its

sculpted abs, low body fat and most importantly moderate muscle development.

The rise in popularity of this body type was connected to the growth of the gym

and fitness industry. While gyms had previously been filthy, underground

bunkers (often tagged onto a boxing club), in the 1980s they became luxurious

health clubs and gym membership became a standard work bonus for white-collar

professionals. Now, having a lithely muscled physique became the goal of the

average professional who would often train after his day at the office.

The

rise in popularity in the Men's Health-type physique meant that bodybuilding -

as a competitive sport - had to assert itself as something different or more

extreme from this body type. With advancements in training, nutrition, and

pharmaceutical drugs (where once steroids were the only chemical recourse,

growth hormone, insulin, and others were also being used), competition level bodies

started to become more extreme and pushed the envelope out in relation to

muscular development.

However,

the key factor which is certainly implied in the above discussion of the Men's

Health physique and the Adonis Complex is the question of who is doing the

gazing and whether or not this is underpinned by eroticism. As I have argued

already, the investment in the "freakishness" of extreme bodybuilding

fuels fantasies of being released from the pressures of the conventional Adonis

Complex and of sexuality altogether. The subject fantasizes about challenging

these pressures in deconstructive, confrontational fashion rather than simply

ignoring them and being accused of "letting himself go." Similarly

though, one of the reasons why contemporary bodybuilding has embraced the idea

of "freakishness" may well be its paranoid attempt to extricate

itself from the connotation of homoeroticism.

Bodybuilding

has always held an uncomfortable relationship with gay culture. One of the most

famous early "muscle" publications was Bob Mizer's mail-order

Physique Pictorial. This magazine was soft porn masquerading as an exercise

magazine, and featured young toughs as its models (often just out of prison)

whose physiques ranged from "some" muscular development to none at

all. One of the reasons why gay soft porn stopped disguising itself as a

bodybuilding publication was simply the question that the pornography

legislation changed in the 1970s and porn could now legally exist. No longer

did porn fans have to buy publications which claimed to be dedicated to

"sun bathing enthusiasts" and but could buy actual pornography.

Indeed, one of the Weiders' biggest struggles - and their bodybuilding

ambassador Arnold Schwarzenegger was very important here - was to free

bodybuilding from the taint of homosexuality. Schwarzenegger's indisputable

heterosexuality and charisma greatly helped in erasing the stigma of bodybuilders

as closet gays.

However,

the rise in the 1980s of gay pornography, which became a mulit-million dollar

enterprise, reified the representation of the classical bodybuilder's physique

as ultimate object of homoerotic desire. While images of bodybuilders engaging

in homosexual activities had previously been the stuff of fantasy drawings,

such as those produced by Tom of Finland, now these could be watched on home

videotape. Of the gay pornography studios, Falcon became synonymous with the

bodybuilder look and often featured impoverished amateur bodybuilders having

sex with other bodybuilders. Of course, these bodybuilders had more in common

with the type of physique predating Schwarzenegger than with the "mass

monster" or "freak" of the 1980s competition world. (This, of

course, was why they were impoverished, as their physiques had not attained the

"freakish" proportions necessary to gain entry to the professional

ranks.) Therefore, while the classical physique was being crowned as the ultimate

in homoeroticism, with gay men (especially those based in metropolitan

settings) taking up bodybuilding as a serious hobby, professional bodybuilding

needed to distinguish itself from that look and so espoused the excessive,

grotesque physique.

Another

factor in this debate may well have been the lasting impact of early 1980s

professional bodybuilder Bob Paris. Paris was (and still is) the only

professional bodybuilder to have taken the very brave step of announcing his

homosexuality to the bodybuilding world. A noted writer and critic Paris has

written a considerable amount about his experiences of professional

bodybuilding and has always maintained that "coming out" was damaging

for his career. As the only openly gay professional bodybuilder, Paris has

attained iconic status within gay culture. For example, London's most famous

gay gym is The Paris Gym, although, sadly, many of the gym-goers training in it

nowadays are unlikely to be aware of the significance of the gym's name. Yet

Paris is not only famous for being openly gay identified but also for arguing

that the classical physique should remain the goal of professional

bodybuilding. Writing about the shift in professional bodybuilding toward

freaky, grotesque proportions in Straight From the Heart: A Love Story, Paris

argued:

- By the time I had stopped competing, I hated

bodybuilding and the direction it was headed in. And, in fact, I still disagree

with the direction the sport was and is taking. I saw bodybuilding as a road

toward the 'perfect' physical specimen. The dominant culture of the sport for

the last ten years has been grotesque freakiness for the sake of freakiness.

(1994)

What

this did, of course, was help cement the link between the classical body and

homosexuality. If Paris, an openly gay man, exalted the "beauty" of

the classical physique, then most people interpreted that this was a look which

appealed to gay men. If bodybuilding was not to be a homoerotic beauty pageant,

then it needed to transform the look of the bodies on the stage. Indeed, this

emphasis on how a bodybuilding competition should not be read as a beauty

contest, and how those men were not hunk pinups, was exemplified by one of the

most popular "mass-monsters" of the late 1980s/early 1990s - Nasser

el Sonbaty. The journalist Jon Hotten described Sonbaty as having 'the head of

a professor . . . and the body of a genuine freak.' Sonbaty did indeed have the

stereotypical head of the professor even in the strictly physical sense given

that he was balding - yet did not simply shave the head but emulated a style

which was not far from being labeled a "comb-over" - and always wore

a pair of big, thick specs - even on the competition stage. Sonbaty's specs

were not fashion glasses but heavy, unglamorous spectacles. Yet beneath this

professorial-looking head was a physique which, at a height of 5/11",

often weighed an astonishing 300 obs plus. Sonbaty's appearance certainly made

the point: professional competitive level bodybuilding is not a beauty contest

and the contestants on stage are not hunk pinups.

Conclusion

This

chapter has argued that in order for professional-level bodybuilding to survive

it had to change its strategy of publicity representations and market itself as

a postmodern freak show. Given the rise in female bodybuilding, the cultural

trend of the Adonis Complex, and the growing articulation of a metropolitan gay

bodybuilding culture, contemporary professional bodybuilding had to repackage

itself as something different from the canonization of male beauty. Enfreakment

discourse became the accepted way of marketing professional bodybuilders to the

fans. I have suggested that these representations may fuel homosocial,

bigorexic fantasies for the bodybuilding fan; the idea of challenging regimes

of normative attractiveness and creating a body which moves outside the

dynamics of sexuality altogether.

However,

it should be remembered that, historically, the freakshow was a place where

human deviance was valuable, and in t hat sense valued. Joshua Gamson points

out that this "value" is the way in which the "freak" can

challenge received dictates of normativity (Freaks Talk Back: Tabloid Talk

Shows and Sexual Nonconformity). Indeed, Gamson argues that one contemporary

evolution of the freak show - the daytime chat show - is not simply a vehicle

for permitting normative people to stare at the freaks but can also be read as

spectacles which 'mess with the "normal," giving hours of play and

often considerable sympathy to stigmatized populations, behaviors, and

identities, and at least pertly muddying the waters of normality' which,

arguably, intrigues most critics interested in enfreakment.

Perhaps

the final word should be with Greg Valentino who in his own charming style

states that the fans of bodybuilding demand the disquieting pleasure of

watching "freaks":

- In bodybuilding nobody gives a shit about

Milos Sarcev up there all symmetrical with a beautiful body. You ask the crowd

who they like to see. They like to see the freaks, Markus Ruhl of Paul Dillet,

even though he can't pose to save his life. People love to see mass. They like

to see freaks. It's what gets them into this sport.

And

what the fans want - the fans shall get.

0 comments:

Post a Comment